COMMUNITY DESIGNED PUBLIC SPACES

18 Jul 2017

Minecraft, a popular world building video game, is changing the face of who we involve in the development of our public spaces. Youths worldwide are working with the UN to design future spaces.

The Block by Block project is the work of UN-Habitat – the United Nations agency for sustainable urban development – together with the makers of the hugely popular world-building computer game Minecraft, Mojang.

Minecraft is the world's second best-selling video game of all time, with more than 121 million copies sold worldwide. In a virtual landscape, players use textured cubes to build constructions. There are no specific goals set for the player to accomplish, so the world building is completely user motivated and designed.

Minecraft is being used as a community participation tool in the design of public spaces in more than 25 countries since 2012. The Block by Block project reaches out in particular to young people, women and slum dwellers, to help inform the needs of the community in the design of local public spaces. Kenya, Peru, Haiti and Nepal are among the nations to have Block by Block-designed spaces.

Last month, Pontus Westerberg, coordinator of Block by Block, took to the stage at Made in Space, a three-day festival held at Space10 in Copenhagen's meatpacking district, to explain how the initiative uses Minecraft as a community participation tool in urban design for public space projects all over the world – particularly in poor communities within developing countries.

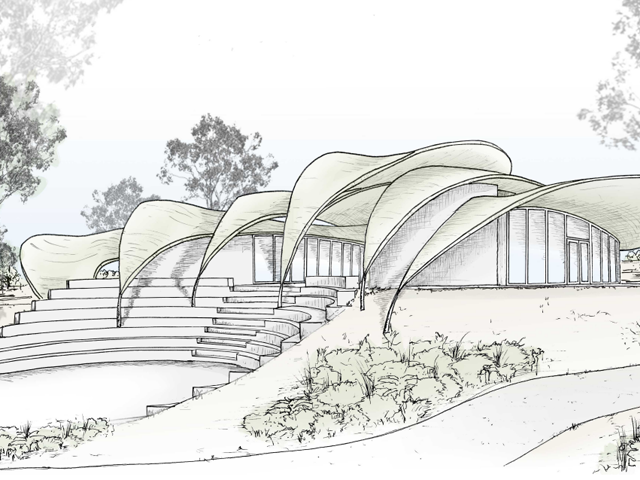

Communities are able to build into virtual landscapes that correspond to the real-life environment, as in this project in Mogadishu, Somalia, where a market hall has been built on a former waste heap.

This rendering shows plans for the second phase of the Market Hall development in Mogadishu, Somalia, where 20 years of civil war has severely limited the development of basic urban services.

Speaking about typical urban planning meetings in local communities, Westerberg says, “They're quite stale. Generally, a person will stand in a room in front of people who are listening. All the people in the room are above the age of 45 or 50. There are generally no young people, and not so many women."

"In Kenya where I live, more than 50 per cent of the population is under 25, so finding ways to get young people involved in community space projects is crucial."

To bring the wider community in on this process, the Block by Block programme organises workshops with 30-to-50 people that live and work around the planned public spaces. Divided into groups of around three or four people, the local residents are taught how to build in the virtual landscape of Minecraft.

"Older residents who have never used computers before are taught by young guys," explained Westerberg. "So you get this really nice intergenerational communication going on."

After building projects in Minecraft, stakeholders from local government, the mayor's office, planners and architects listen to presentations by people who were part of the design process.

Speaking about one particular project in Nairobi, Kenya, Westerberg said, "I spoke to the mayor of Nairobi and the head of the urban planning department after the presentations, and they were just amazed to see that young women from slums could actually design as architects or urban planners."

The ideas from the presentations are put into a final report, which is then given to an architect, who translates the designs and ideas into architectural drawings.

Jose Sanchez, the developer behind another architecture-focused video game, Block'hood, told Dezeen last year that the medium was becoming an increasingly important tool for designing cities.

"As architects, we have been trained to think of local scales: small, medium, large and extra-large," he said. "But today we face global issues and we need new tools to address a new kind of scale: a planetary scale.

"By using games, we can engage a global audience in the problems that architecture is facing."

MORE NEWS

HARNESSING THE POWER OF DESIGN TO TRANSFORM CITIES

JARRAHDALE TRAIL CENTRE TAKES DESIGN CUES FROM NATIVE FLORA

WOOD CARVING WITH BRANDON KROON

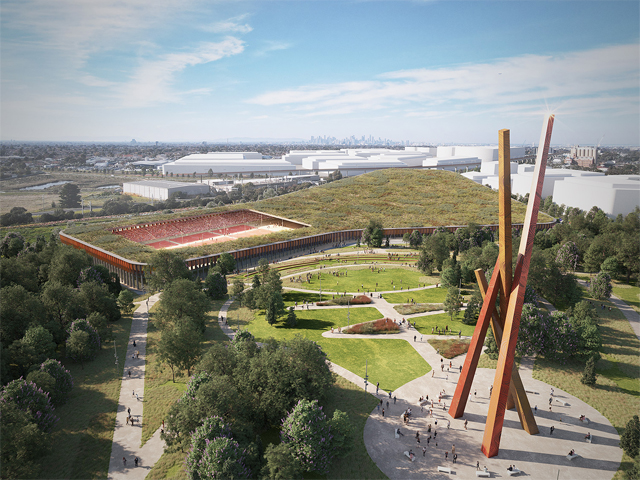

MELBOURNE'S NEW PARK ON A FORMER LANDFILL SITE

MASTERPLAN FOR INCLUSIVE, CLIMATE-RESILIENT COMMUNITY PARK IN LISMORE