VISIONS OF UTOPIA

09 Oct 2019

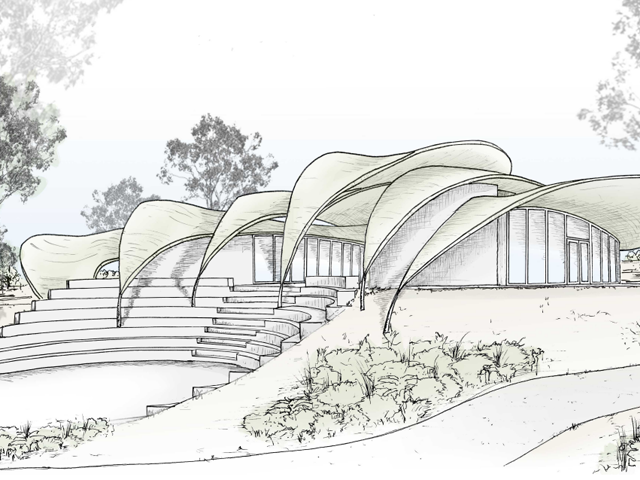

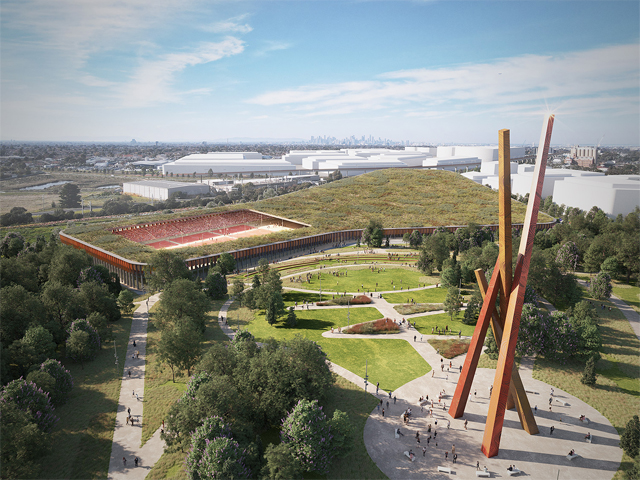

Lagoon beaches, an Indigenous memorial and floating pods that create an island are just some of the 31 proposals that have been shortlisted for the new Future Park development in Melbourne.

Landscape architects from 20 countries submitted 125 entries to the international competition for a 'Future Park' within 10 kilometres of the city centre.

“The whole idea of the competition is to stretch our understanding of what open space could be,” says Jillian Walliss, senior lecturer in landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne and a co-organiser of the event.

The competition, co-hosted by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA), operates on a level playing field: all entries are anonymous.

The designer of the winning scheme and the recipients of the $20,000 prize pool will be announced in Melbourne on October 11 as part of the 2019 International Festival of Landscape Architecture.

There is an urgent issue that underlies the competition: Melbourne’s rapidly increasing population and a perceived lack of planning. Melbourne is considered the fourth-fastest-growing city in the OECD; by 2050 it is expected to eclipse Sydney as Australia’s largest city.

“We’re reacting to the way open space is missing in the planning of Melbourne,” says Walliss. “Encouraging density hasn’t been balanced out with an investment in bigger public amenity.”

Melbourne may be renowned for its 19th-century parks circling the CBD but today, static, picturesque parks aren’t enough. Nor is the antidote in simple sporting fields, contentiously termed ‘green deserts’.

“It’s less about the park as an open space and more about what it can do in the function of the city,” says the competition’s chief judge, Jacky Bowring, a professor of landscape architecture at Lincoln University in New Zealand.

Parks offer places for children to play and combat social isolation, and they encourage exercise. For the environment, parks help flood mitigation and tackle climate change and urban heat island effects. They also encourage biodiversity.

“Parks are green infrastructure,” says Walliss. “Its mechanisms make our environment and our cities healthy. The pocket park is a very limited model. Quite often it’s just space that’s left over. All the rules of systems work against you. If you want ecological and social value, then a more systematic approach is necessary.”

Judging for the Future Park competition hinges on two fundamental issues: where will the park go and how will it function?

The ambitious Melbourne Dynan Valley 2050 bid proposes greening the railway spine from Richmond to Footscray, creating Aboriginal heritage trails, a beach, an urban farm and a wildlife sanctuary, to name only a few ideas.

The National Biodiversity Network goes beyond Melbourne to create ecological corridors nationwide. It imagines a political push to create a biodiversity network with bee corridors and butterfly highways.

Perhaps the most controversial proposal is one that dares to move Queen Victoria Market and transform the site and its nearby Indigenous cemetery into a memorial park that connects with Flagstaff Gardens. The relocated market at Moonee Creek would be encircled by housing, greenspace and urban agriculture.

Professor Bowring says, “As designers, we’re imagining utopias, the perfect version of the world. All these different versions of utopia mirror back what designers think are important about contemporary society at the time.”

What the public thinks is important will be up for debate in a public lecture where winners and the jury will discuss the projects.

The Future Park exhibition is at Dulux Gallery, Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne, from October 4 to November 1.

The Future Park Competition Public Lecture is at Glyn Davis Building, University of Melbourne, B117 Theatre, Basement Level, on October 14, 6.30pm to 7.30pm.

Via The Age

MORE NEWS

MASTERPLAN FOR INCLUSIVE, CLIMATE-RESILIENT COMMUNITY PARK IN LISMORE

JARRAHDALE TRAIL CENTRE TAKES DESIGN CUES FROM NATIVE FLORA

STRIKING GOLD IN BALLARAT

MELBOURNE'S NEW PARK ON A FORMER LANDFILL SITE

WOOD CARVING WITH BRANDON KROON